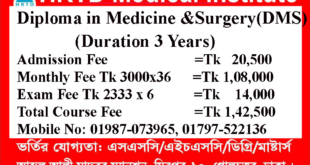

2 Years DMS Course Details

Mobile Number 01797522136, 01987073965, Hotline- 01969947171. 2 Years DMs Course is a long Diploma in Medicine & Surgery course in Bangladesh. This Course is available in HRTD Medical Institute. HRTD Medical Institute is reputed and popular for 3 Years DMA Course, Pharmacy Courses, Diploma Medical Assistant Courses, etc. HRTD Medical Institute is an organization of HRTD Limited which is Registered by the Govt of the People Republic of Bangladesh.

Total Cost for 2 Years DMS Course

Total Cost =92500 tk

Admission fee =16500 tk

Monthly fee (3000×24) = 72000 tk

Exam fee 4 semester =4000 tk

Location for 2 Years DMS Course

HRTD Medical Institute, Abdul Ali Madbor Mansion, Folpotty Mosjid Goli (Bitul Mamur Jame Mosjid Goli), Plot No. 11, Metro Rail Piller No. 249, Mirpur 10 Golchattar, Dhaka.

Document for Admission in 2 Years DMS Course

2 Years DMS Course Photocopy of Certificate, Photocopy of NID, Passport Size Photo 4 Pcs. Without NID, a Birth Certificate is allowed for an emergency case.

Admission Eligibility for 2 Years DMS Course

2 Years DMS Course Admission Eligibility. Mobile Number. 01987073965. 01941123488, 01797522136. SSC or Equivalent/HSC/ Degree/Master’s from any Background (Science/ Arts/ Commerce/ Technical).

Class System for 2 Years DMS Course

Class System for 2 Years DMS Course in Dhaka: Weekly Class 3 hours. For jobholders, 3 hours a day. The option days are Friday Morning Shift from 9:00 AM to 12:00 PM, Friday Evening Shift from 3:00 PM to 6:00 PM, Monday Morning Shift from 9:00 AM to 12:00 PM, and Monday Evening Shift from 3:00 PM to 6:00 PM. Saturday Morning Shift from 10am to 1 Pm, Evening Shift from 3 pm to 6 pm.

For Regular Students, Saturday 1 hour, Monday 1 hour, and Friday 1 hour. Morning Shift From 9:00 AM to 12:00 PM, and Evening Shift From 3:00 PM to 6:00 PM.

Hostel Facilities in HRTD Medical Institute for 2 Years DMS Course

Hostel & Meal Facilities

The Institute has hostel facilities for the students. Students can take a bed in the hostel.

Hostel Fee Tk 3000/- Per Month

Meal Charges Tk 3000/- Per Month. ( Approximately )

হোস্টাল ও খাবার সুবিধা

ইনস্টিটিউটে শিক্ষার্থীদের জন্য হোস্টেল সুবিধা রয়েছে। ছাত্ররা হোস্টেলে বিছানা নিতে পারে।

হোস্টেল ফি 3000/- টাকা প্রতি মাসে,

খাবারের চার্জ 3000/- টাকা প্রতি মাসে।(প্রায়)

Address of HRTD Medical Institute for 2 Years DMS Course

আমাদের ঠিকানাঃ HRTD মেডিকেল ইন্সটিটিউট, আব্দুল আলী মাদবর ম্যানশন, সেকশন ৬, ব্লোক খ, রোড ১, প্লট ১১, মেট্রোরেল পিলার নাম্বার ২৪৯, ফলপট্টি মসজিদ গলি, মিরপুর ১০ গোলচত্ত্বর, ঢাকা ১২১৬ । মোবাইল ফোন নাম্বার ০১৭৯৭৫২২১৩৬, ০১৯৮৭০৭৩৯৬৫ ।

Our Address: HRTD Medical Institute, Abdul Ali Madbor Mansion, Section-6, Block- Kha, Road- 1, Plot- 11, Metro Rail Pilar No. 249, Falpatty Mosjid Goli, Mirpur-10 Golchattar, Dhaka 1216. Mobile Phone No. 01797522136, 01987073965.

Teachers For 2 Years DMS Course

- Dr. Md. Sakulur Rahman, MBBS, CCD (BIRDEM), Course Director

- Dr. Sanjana Binte Ahmed, BDS, MPH, Assistant Course Director

- Dr. Tisha, MBBS, PGT Gyne, Assistant Course Director

- Dr. Suhana, MBBS, PGT Medicine

- Dr. Danial Hoque, MBBS, C-Card

- Dr. Tisha, MBBS

- Dr. Afrin Jahan, MBBS, PGT Medicine

- Dr. Ananna, MBBS

- Dr. Lamia Afroze, MBBS

- Dr. Amena Afroze Anu, MBBS, PGT Gyne, Assistant Course Director

- Dr. Farhana Antara, MBBS,

- Dr. Nazmun Nahar Juthi, BDS, PGT

- Dr. Farhana Sharna, MBBS

- Dr. Bushra, MBBS

- Dr. Turzo, MBBS

- Dr. Kamrunnahar Keya, BDS, PGT (Dhaka Dental College)

- Dr. Shamima, MBBS, PGT Gyne

- Dr. Alamin, MBBS

- Dr. Benzir Belal, MBBS

- Dr. Disha, MBBS

- Dr. Mahinul Islam, MBBS

- Dr. Tisha, MBBS, PGT Medicine

- Dr. Anika, MBBS, PGT

- Dr. Jannatul Ferdous, MBBS, PGT Gyne

- Dr. Jannatul Aman, MBBS, PGT

- Dr. Rayhan, BPT

- Dr. Abu Hurayra, BPT

- Dr. Sharmin Ankhi, MBBS, PGT Medicine

- Md. Monir Hossain, B Pharm, M Pharm

- Md. Monirul Islam, B Pharm, M Pharm

- Md. Feroj Ahmed, BSc Pathology, PDT Medicine

Practical class for 2 Years DMS Course

- Heart Beat, Heart Rate

- Heart Sound, Pulse

- Blood Pressure, Hypertension, Hypotension

- First Aid Box

- Auscultation

- Inhaler, Rota haler

- Nebulizer

- Glucometer Blood Glucose

- Injection I/V

- Injection I/M

- Cleaning, Dressing, Bandaging

- Saline

- CPR

- Stitch

- Body Temperature

- Nasal Tube Gel ,Hand Wash

- Blood Grouping

- Cyanosis, Dehydration Test, Edema Test

Heart Beat, Heart Rate for 2 Years DMS Course

Heart Beat for 2 Years DMS Course

Measuring your heart rate—often referred to in a practical or laboratory setting as a “pulse check”—is one of the most fundamental skills in biology and clinical medicine. It provides an immediate window into the cardiovascular system’s efficiency, reflecting how hard the heart is working to deliver oxygen-rich blood to the body’s tissues. Whether you are a student conducting a classroom experiment to see how physical exertion changes your physiology or an individual monitoring your fitness progress, understanding the mechanics of a “heartbeat practical” is both educational and highly useful for long-term health tracking.

The heart functions as a muscular pump that contracts rhythmically, governed by internal electrical signals starting at the sinoatrial (SA) node. Each contraction, or systole, forces blood through the arteries, creating a “pulse” wave that can be felt at various points where an artery runs close to the skin and over a bone.

1. How to Manually Measure Heart Rate

To perform a basic heartbeat practical, you only need your fingers and a timing device like a stopwatch.

- Location Choice (Pulse Points):

- Radial Pulse: Found on the thumb side of the inner wrist. This is the most common site for routine checks.

- Carotid Pulse: Located on the side of the neck, in the groove beside the windpipe. This is often easier to find during or immediately after intense exercise.

- The Procedure:

- Preparation: Sit quietly for five minutes to establish a true resting heart rate.

- Finger Placement: Use the pads of your index and middle fingers. Never use your thumb, as it has its own pulse and can lead to inaccurate counting.

- Pressure: Apply firm but gentle pressure until you feel a rhythmic thumping or tapping sensation.

- Counting: Look at your stopwatch. Count the number of beats you feel for 30 seconds and then multiply that number by 2 to get your beats per minute (BPM). Alternatively, count for 15 seconds and multiply by 4 for a quicker result.

2. Common Classroom Experiments

In many biology courses (such as GCSE or A-Level), the “Heart Beat Practical” involves investigating how specific variables affect the pulse.

- Effect of Exercise: This is the most standard experiment. Students measure their resting heart rate, then perform a set activity (like jogging on the spot or doing star jumps) for one to two minutes. The heart rate is measured immediately after exercise and then every minute thereafter to calculate recovery time—the time it takes for the heart to return to its resting state.

- Postural Changes: This practical examines how the heart adapts when moving from a lying position to sitting, and finally to standing. Because gravity makes it harder for blood to return to the heart when standing, the heart rate typically increases slightly to maintain blood pressure.

- Stimulants (Daphnia Experiment): Advanced biology students may use a microscope to observe the heart rate of a small crustacean called Daphnia. By adding drops of caffeine or alcohol to the water, they can directly observe how these substances increase or decrease the heart’s pumping speed.

3. Understanding Your Results

Once you have collected your data, interpreting it requires knowing the “normal” physiological ranges for humans in 2025:

- Resting Heart Rate (RHR): For most adults, a normal RHR is between 60 and 100 BPM.

- Athletic Advantage: Highly fit individuals or professional athletes often have RHRs as low as 40–50 BPM because their heart muscle is stronger and more efficient at pumping blood.

- Maximum Heart Rate: A common formula used to estimate the upper limit of your heart’s capacity is 220 minus your age. During vigorous exercise, target heart rates are usually 70–85% of this maximum.

Clinical and Safety Considerations

While manual pulse checks are a great starting point, clinicians often use more advanced methods for a “practical” diagnosis. For instance, an Electrocardiogram (ECG) measures the electrical activity of the heart to identify irregular rhythms (arrhythmias). Additionally, a stethoscope allows for auscultation, where the “lub-dub” sounds of the heart valves closing are directly monitored.

If you find that your resting heart rate is consistently above 100 BPM (tachycardia) or below 60 BPM for a non-athlete (bradycardia), it is advisable to consult a healthcare provider, especially if accompanied by symptoms like dizziness or palpitations

Heart Beat for 2 Years DMS Course

Understanding the mechanics of the human heart through practical application is a foundational exercise in biology and medicine. The “heartbeat” is not just a sound; it is the physical manifestation of the cardiac cycle—the sequence of contraction (systole) and relaxation (diastole) that propels blood throughout the body. In a practical laboratory or home setting, measuring these beats allows us to observe how the body maintains homeostasis by adjusting blood flow in response to different stimuli, such as physical exertion, stress, or even temperature changes.

1. Methods of Measuring Heart Rate

In a practical setting, heart rate is typically measured as a “pulse rate,” which is the rhythmic expansion of an artery as blood surges through it after each contraction of the left ventricle.

- Radial Pulse (Wrist):

- Place your index and middle fingers on the thumb side of the inner wrist.

- Press firmly until you feel the “thump” of the artery against the bone.

- Pro Tip: Avoid using your thumb to measure another person’s pulse, as your thumb has its own strong pulse that can lead to an inaccurate count.

- Carotid Pulse (Neck):

- Locate the groove on either side of the windpipe (trachea), just under the jawline.

- Press gently with two fingers.

- Warning: Never press both carotid arteries at the same time, as this can restrict blood flow to the brain and cause fainting.

- Auscultation (Stethoscope):

- Place the diaphragm of the stethoscope on the chest, slightly to the left of the sternum.

- Listen for the “lub-dub” sound. One “lub-dub” equals one complete heartbeat.

2. Practical Step-by-Step Experiment

This experiment aims to investigate how physical activity affects heart rate.

- Baseline Measurement (Resting Heart Rate):

- Sit or lie down in a calm environment for at least five minutes.

- Measure your pulse for 60 seconds (or 30 seconds and multiply by 2).

- Record this value. A normal resting rate for adults is typically 60–100 beats per minute (bpm).

- Activity Phase:

- Perform a set activity (e.g., jogging on the spot or jumping jacks) for 1–2 minutes.

- Immediately after stopping, measure your pulse for 15 seconds and multiply by 4 to get the instantaneous “active” heart rate.

- Recovery Phase:

- Sit back down and measure your pulse every minute for the next five minutes.

- A fit cardiovascular system will return to the resting baseline more quickly than an unfit one.

3. Understanding the Physiology

- The “Lub-Dub”: The first sound (“lub”) is caused by the closing of the atrioventricular valves when the ventricles contract. The second sound (“dub”) occurs when the semilunar valves close as the ventricles relax.

- Why Heart Rate Increases: During exercise, muscle cells require more oxygen and glucose for respiration. The nervous system signals the heart to beat faster and with more force to deliver oxygenated blood and remove waste products like carbon dioxide.

- Factors Influencing Results:

- Emotions: Stress or anxiety can trigger the “fight or flight” response, raising the heart rate.

- Temperature: High heat and humidity force the heart to pump more blood to the skin to facilitate cooling, increasing the rate.

- Fitness: Athletes often have much lower resting heart rates (sometimes 40–60 bpm) because their heart muscle is more efficient.

Summary of Key Clinical Terms

- Tachycardia: A resting heart rate consistently over 100 bpm.

- Bradycardia: A resting heart rate consistently below 60 bpm (unless you are a highly trained athlete).

- Arrhythmia: An irregular rhythm where the intervals between beats are not equal.

Subjects for 2 Years DMS Course

2 Years DMS Course Contains 18 Subject. Mobile Number: 01987-073965,01797-522136

- Human Anatomy & Physiology-1

- Pharmacology-1

- Study of OTC Drugs

- First Aid-1 & 2 and Practice of Medicine

- Hematology and Pathology for Medical Practice

- Surgery-1 and Antimicrobial Drugs

- Cardiovascular Anatomy

- Medical Diagnosis-1&2

- Chemistry and Medical Biochemistry

- Orthopedic Anatomy

- General Pathology-1

- Pharmacology-2

- Practice of Medicine 2&3

- Essential Drugs

- Neuro Anatomy & Physiology

- Gastrological Drugs and Pharmacology

- Human Anatomy & Physiology-2

- Geriatric Disease and Treatment

Subjects Details for 2 Years DMS Course

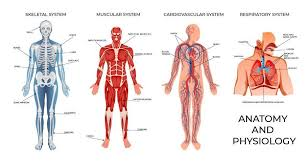

Anatomy & Physiology for 2 Years DMS Course

2 Years DMS Course Anatomy and physiology are the two fundamental pillars of the life sciences, serving as the essential roadmap for understanding how the human body is constructed and how it operates in harmony to maintain life. While they are distinct disciplines, they are virtually inseparable; anatomy focuses on the physical “map” of the body, identifying structures from the microscopic to the macroscopic level, while physiology explains the “mechanics” of how these structures perform their vital functions. Together, they provide a comprehensive picture of the human organism as a highly integrated biological machine.

অ্যানাটমি এবং ফিজিওলজি হল জীবন বিজ্ঞানের দুটি মৌলিক স্তম্ভ, যা মানবদেহ কীভাবে তৈরি হয় এবং জীবন বজায় রাখার জন্য এটি কীভাবে সামঞ্জস্যপূর্ণভাবে কাজ করে তা বোঝার জন্য অপরিহার্য রোডম্যাপ হিসেবে কাজ করে। যদিও এগুলি পৃথক শাখা, তারা কার্যত অবিচ্ছেদ্য; অ্যানাটমি শরীরের ভৌত “মানচিত্র”-এর উপর দৃষ্টি নিবদ্ধ করে, অণুবীক্ষণিক থেকে ম্যাক্রোস্কোপিক স্তর পর্যন্ত কাঠামো চিহ্নিত করে, অন্যদিকে ফিজিওলজি এই কাঠামোগুলি কীভাবে তাদের গুরুত্বপূর্ণ কার্য সম্পাদন করে তার “যান্ত্রিকতা” ব্যাখ্যা করে। একসাথে, তারা একটি অত্যন্ত সমন্বিত জৈবিক যন্ত্র হিসাবে মানবদেহের একটি বিস্তৃত চিত্র প্রদান করে।

The Definition and Scope of Anatomy

Anatomy, derived from the Ancient Greek word anatomē meaning “dissection,” is the study of the structure and physical relationships between body parts. It is primarily a descriptive science that answers the question “What is it?” and “Where is it located?”. The field is typically divided into two major branches based on the scale of observation:

1.Gross (Macroscopic) Anatomy: This involves the study of large structures that are visible to the naked eye without the aid of magnification. It can be approached systemically, which focuses on organ systems like the skeletal or muscular systems, or regionally, which examines all structures in a specific area of the body, such as the head or thorax.

2.Microscopic Anatomy: This branch requires the use of specialized instruments to see structures too small for the human eye. It includes cytology, the study of individual cells and their internal components, and histology, the study of how groups of similar cells work together as tissues.

Historically, the study of anatomy was advanced through the dissection of cadavers, a practice championed by figures like Herophilus, often called the “Father of Anatomy”. Modern anatomy has been revolutionized by non-invasive medical imaging techniques like MRI, CT scans, and ultrasound, which allow clinicians to view the internal structures of living patients with incredible precision.

The Definition and Scope of Physiology 2 Years DMS Course

2 Years DMA Course. Physiology is the dynamic counterpart to anatomy, focusing on the chemical and physical processes that occur within the body to keep an organism alive and healthy. If anatomy is the study of the hardware, physiology is the study of the software and electricity that makes it run. It answers the question “How does it work?”.

Physiologists often focus their research on specific levels of biological organization, ranging from cellular physiology (how chemical reactions power a single cell) to organ-system physiology (how the heart, blood vessels, and blood work together to circulate oxygen). This field relies heavily on concepts from physics and chemistry to explain complex phenomena like electrical signaling in nerves or the exchange of gases in the lungs.

The Principle of Complementarity

A core concept in these disciplines is the Complementarity of Structure and Function, which states that the shape and organization of a body part are intimately tied to its specific function. For example, the thin, flat shape of the air sacs (alveoli) in the lungs is perfectly suited for the rapid diffusion of gases, whereas the thick, muscular walls of the heart’s ventricles are designed to generate the high pressure needed to pump blood throughout the entire body.

Levels of Biological Organization

The human body is organized into a hierarchy of increasing complexity, often categorized into six primary levels:

- Chemical Level: The most basic level, consisting of atoms (like carbon and oxygen) that combine to form molecules (like water and proteins).

- Cellular Level: The smallest independently functioning unit of a living organism, formed when molecules interact to create organelles and membranes.

- Tissue Level: Groups of similar cells that work together to perform a specific task, such as muscle tissue for movement or nervous tissue for signaling.

- Organ Level: A structure composed of two or more different types of tissues that perform a complex biological function, such as the stomach or the brain.

- Organ System Level: A group of organs that cooperate to meet a major physiological need, such as the digestive system breaking down food and absorbing nutrients.

- Organismal Level: The highest level of organization, representing the total human being where all organ systems function together to maintain life and health.

Homeostasis: The Goal of Physiology for 2 Years DMS Course

The ultimate purpose of most physiological processes is to maintain homeostasis, which is the state of steady internal conditions maintained by living things. Despite constant changes in the external environment—such as extreme heat or a lack of food—the body uses complex feedback loops to keep internal variables like temperature, blood pH, and blood sugar within a narrow, healthy range. When homeostasis is disrupted and cannot be restored, the result is often illness, disease, or even death.

Understanding these concepts is not just for medical professionals; it is vital for personal health literacy. Knowledge of anatomy and physiology empowers individuals to interpret medical news, understand the implications of nutrition and medications, and make informed decisions when faced with illness.

Whether you are looking into the regional structures of the human skull or the complex physiology of the urinary system, this field offers a lifelong journey of discovery into the biological machinery that defines our existence. Feel free to ask if you would like to dive deeper into a specific system, such as the cardiovascular or nervous system

Pharmacology-1 for 2 Years DMS Course

“Pharmacology-1” is an introductory course that covers the fundamental principles of pharmacology, including how drugs interact with the body and their initial applications in treating specific organ systems. It is a foundational subject for students in medical, pharmacy, nursing, and other health science fields.

ফার্মাকোলজি-১” হল একটি প্রাথমিক কোর্স যা ফার্মাকোলজির মৌলিক নীতিগুলি কভার করে, যার মধ্যে রয়েছে ওষুধগুলি কীভাবে শরীরের সাথে মিথস্ক্রিয়া করে এবং নির্দিষ্ট অঙ্গ সিস্টেমের চিকিৎসায় তাদের প্রাথমিক প্রয়োগ। এটি চিকিৎসা, ফার্মেসি, নার্সিং এবং অন্যান্য স্বাস্থ্য বিজ্ঞান ক্ষেত্রের শিক্ষার্থীদের জন্য একটি মৌলিক বিষয়।

Core Concepts for 2 Years DMS Course

The initial pharmacology course typically focuses on the core principles that govern all drug action.

- Pharmacokinetics: This describes “what the body does to the drug” and involves four key processes:

- Absorption: The movement of the drug from its administration site into the bloodstream.

- Distribution: How the drug is dispersed throughout the body’s tissues and fluids.

- Metabolism: The breakdown of the drug into metabolites, primarily in the liver.

- Excretion: The elimination of the drug and its metabolites from the body, mainly through the kidneys.

- Pharmacodynamics: This describes “what the drug does to the body” and focuses on the mechanisms of drug action. Key aspects include drug-receptor interactions, dose-response relationships, efficacy, potency, and the therapeutic index (safety margin).

- Drug Classification and Nomenclature: Students learn the different names for drugs (chemical, generic, and brand) and how they are categorized based on their chemical properties or therapeutic uses.

- Routes of Administration: The course covers various methods of delivering drugs into the body (e.g., oral, intravenous, intramuscular, topical) and the advantages and disadvantages of each.

- Adverse Drug Reactions and Interactions: A key component is understanding the potential unwanted effects of drugs and how different medications, foods, or supplements can interact with each other.

- Drug Discovery and Development: The basic phases of clinical trials and the regulatory process for new drug approval are often introduced.

Key Drug Classes Covered for 2 Years DMS Course

Following the general principles, the course often introduces drugs that affect the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the cardiovascular system.

- Drugs Acting on the Autonomic Nervous System:

- Cholinoceptor-activating and blocking drugs (parasympathomimetics and parasympatholytics).

- Adrenoceptor agonists and antagonists (sympathomimetics and sympatholytics).

- Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs:

- Antihypertensive agents.

- Diuretics.

- Drugs for heart failure, angina, and arrhythmias.

- Agents used in coagulation disorders (anticoagulants, antiplatelets, thrombolytics).

- Lipid-regulating drugs (statins, fibrates).

- Other Systems: Depending on the specific curriculum, the course might also cover an introduction to drugs for the central nervous system (CNS), local anesthetics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Study of OTC Drugs for 2 Years DMS Course

The study of Over-the-Counter (OTC) drugs is a multifaceted discipline primarily situated within Pharmacology and Pharmaceutical Science. This field examines the mechanisms, safety, and societal impact of non-prescription medications—those sold directly to consumers without a physician’s order.

ওভার-দ্য-কাউন্টার (ওটিসি) ওষুধের অধ্যয়ন মূলত ফার্মাকোলজি এবং ফার্মাসিউটিক্যাল বিজ্ঞানের মধ্যে অবস্থিত একটি বহুমুখী শাখা। এই ক্ষেত্রটি প্রেসক্রিপশনবিহীন ওষুধের প্রক্রিয়া, সুরক্ষা এবং সামাজিক প্রভাব পরীক্ষা করে – যা সরাসরি ভোক্তাদের কাছে চিকিৎসকের নির্দেশ ছাড়াই বিক্রি করা হয়।

In academic and clinical settings, the study of OTC drugs encompasses several specialized areas of focus.

1. Primary Academic Subjects and Fields

The study of OTC drugs is not a single “subject” but a core component of several degree programs:

- Pharmacology: This is the overarching science of drugs and their effects on living systems. It involves studying drug classes, mechanisms of action (how the drug works at a molecular level), and pharmacokinetics (how the body absorbs and processes the drug).

- Pharmacy: This professional field focuses on the safe dispensing of medications and providing clinical advice to patients. In this subject, OTC drugs are studied in the context of “self-care” and “community pharmacy,” where pharmacists act as the primary interface for patient education.

- Toxicology: Often studied alongside pharmacology, toxicology focuses on the adverse effects and risks of drugs, including the dangers of OTC misuse, such as liver damage from excessive acetaminophen intake.

- Public Health: Researchers study the prevalence of self-medication practices across different populations (e.g., students, elderly, or urban residents) to identify trends, risks like antibiotic resistance, and the need for better health literacy.

2. Core Topics within the Study of OTC Drugs for 2 Years DMS Course

Students and researchers typically explore the following key areas:

- Drug Classification: Identifying which medications are safe for OTC sale (like analgesics and antacids) versus those that require a prescription (like most antibiotics).

- KAP Studies (Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice): These are common research frameworks used to assess how much the public knows about OTC drugs, their attitudes toward them (e.g., whether they believe they are “safe”), and their actual usage habits.

- Safety and Adverse Reactions: Analyzing side effects, drug-drug interactions, and the risks of “masking” serious underlying diseases through self-treatment.

- Regulation and Ethics: Studying the legal frameworks that govern how OTC drugs are marketed, sold, and labeled in various countries (e.g., FDA in the US or PMDA in Japan).

3. Common OTC Drug Categories Studied

Research frequently centers on these prevalent classes of non-prescription medications:

- Analgesics/Antipyretics: Pain and fever relievers like acetaminophen and ibuprofen.

- Cough and Cold Preparations: Decongestants and suppressants like dextromethorphan.

- Gastrointestinal Agents: Antacids, laxatives, and anti-diarrheals.

- Dermatologicals: Medicated skin treatments and antiseptic creams.

- Vitamins and Supplements: Health boosters often used by students for concentration or general well-being.

4. Societal Impact and Trends (2025 Data)

As of 2025, several key trends have been identified in the study of OTC drugs:

- High Prevalence of Self-Medication: Recent studies show that self-medication rates are extremely high, often exceeding 75% in university student populations in regions like Dhaka and Saudi Arabia.

- Misconceptions regarding Antibiotics: A significant global issue remains the public’s incorrect belief that antibiotics are OTC drugs, which leads to misuse and contributes to the public health crisis of antibiotic resistance.

- Economic Drivers: In many countries, the high cost of physician consultations and the convenience of pharmacies are the primary motivators for choosing OTC drugs over professional medical care.

- Influence of Media: Advertisements on social media and TV are increasingly cited as major drivers of consumer choice for OTC products.

In summary, the study of OTC drugs is a vital part of modern healthcare education, focusing on balancing the benefits of accessible self-care with the critical need for patient safety and education. If you are interested in a specific area, such as a particular drug class or regulatory policy, feel free to ask for more detailed information.

First Aid-1 & 2 and Practice of Medicine for 2 Years DMS Course

First Aid 1 & 2 for 2 Years DMS Course

Understanding the concepts of First Aid Levels 1 and 2 is fundamental for anyone looking to bridge the gap between an accident occurring and professional medical services arriving. These levels are structured as a progressive curriculum, starting from the absolute basics of life preservation to more complex casualty management and secondary medical assessments.

The Foundations: First Aid Level 1 for 2 Years DMS Course

First Aid Level 1 serves as the introductory baseline for emergency response. It is designed to equip individuals with the confidence and skills needed to manage day-to-day emergencies and life-threatening situations until paramedics take over.

- Primary Principles and Ethics: Learners are taught the “Three Ps” of first aid: Preserve life, Prevent further injury, and Promote recovery. This stage also covers legal requirements, such as the Good Samaritan principles and the importance of obtaining consent before assisting.

- Scene Assessment (DRSABCD): A cornerstone of Level 1 is the DRSABCD action plan. This involves checking for Danger, checking for a Response, Sending for help, checking the Airway, checking for Breathing, performing CPR, and using a Defibrillator (AED).

- Life-Saving Interventions:

- CPR and Choking: Training focuses on one-person adult and child resuscitation techniques and clearing obstructed airways.

- Bleeding and Wounds: Techniques for controlling severe external bleeding using direct pressure and basic bandaging are critical.

- Shock Management: Recognizing the signs of shock—such as pale, cold, clammy skin—and learning how to position a patient to maintain blood flow to vital organs.

- Common Medical Conditions: Level 1 provides a broad overview of how to respond to fainting, allergic reactions (anaphylaxis), seizures, and minor burns or environmental injuries like stings.

Advancing Skills: First Aid Level 2 for 2 Years DMS Course

First Aid Level 2 is often referred to as “Intermediate First Aid.” It is a comprehensive advancement that includes all Level 1 topics but adds a deeper layer of medical understanding and more complex practical skills.

- Secondary Survey: While Level 1 focuses on the immediate “Primary Survey” (life-threats), Level 2 introduces the Secondary Survey. This is a systematic, head-to-toe physical examination used to identify injuries that are not immediately life-threatening but require attention.

- Advanced Injury Management:

- Musculoskeletal Injuries: Level 2 goes beyond simple bandaging to include splinting for fractures and advanced techniques for managing sprains, strains, and dislocations.

- Specific Trauma: Learners study more detailed responses to chest injuries (like punctured lungs), abdominal injuries, and specialized eye injury care.

- Head and Spinal Injuries: This level emphasizes the “log-roll” technique and other methods to stabilize a patient when a spinal injury is suspected, preventing permanent paralysis.

- Multiple Casualty Management: One of the most challenging aspects of Level 2 is learning how to manage a scene with multiple injured people. This involves triage, or the process of determining which victims require the most urgent care.

- Complex Medical Emergencies: The curriculum expands to include the recognition and immediate management of heart attacks, strokes, and the effects of various poisons.

Key Differences at a Glance

| Feature | First Aid Level 1 | First Aid Level 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Basic life support and immediate response | Advanced assessment and injury stabilization |

| CPR | Usually one-person basic CPR | Includes two-person CPR and advanced techniques |

| Assessment | Primary Survey (Danger/Airway/Breathing) | Includes Secondary Survey (Head-to-toe exam) |

| Environment | General home or office emergencies | Higher-risk workplaces or industrial settings |

Nice-to-Know: The Evolution of Training

The modern concept of first aid training began in 1859 with Henry Dunant, who witnessed the suffering at the Battle of Solferino and later helped found the International Red Cross. Today, these courses are not just for healthcare workers; they are often mandatory for workplace safety officers under occupational health laws to ensure a safe environment for all employees.

For those looking to get certified, organizations like the Red Cross or local vocational training centers offer accredited programs that meet these Level 1 and 2 standards. These certifications typically remain valid for three years, after which a refresher course is recommended to stay current with the latest medical protocols.

Feel free to ask if you would like a detailed breakdown of a specific procedure, such as the exact steps for adult CPR or how to identify different types of shock.

Practice of Medicine for 2 Years DMS Course

The practice of medicine is an ancient and multi-faceted discipline that sits at the intersection of rigorous scientific inquiry and deeply humanistic art. In 2025, it is defined as the integration of individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence to make critical decisions about patient care. While the term often refers to the day-to-day actions of physicians—diagnosing, treating, and preventing disease—it also encompasses a broader legal, ethical, and organizational framework that governs how health is managed globally.

The Dual Nature: Art and Science for 2 Years DMS Course

Modern practitioners often describe medicine as both an art and a science.

- The Science: This involves the application of biomedical sciences, genetics, and medical technology. It relies on “standard empiricism”—the production of objective knowledge that can be publicly tested and verified through research and clinical trials. In 2025, this increasingly includes the use of Precision Medicine and Evidence-Based Practice to tailor treatments to specific genetic profiles.

- The Art: Clinical practice requires “practical wisdom” or phronesis. A computer may be able to process logic, but a human physician interprets “messy details” like a patient’s personal values, socio-economic context, and emotional state to make a final judgment. This humanistic side is essential for establishing the trust necessary for a successful Doctor-Patient Relationship.

The Clinical Encounter

The practice of medicine typically manifests in the clinical encounter, which follows a structured yet adaptable process:

- History Taking: The practitioner reviews medical records and interviews the patient to understand their story, including psychological and social factors.

- Physical Examination: Using tools like a stethoscope, the doctor performs four basic actions—inspection, palpation (feeling), percussion (tapping), and auscultation (listening)—to find objective signs of illness.

- Differential Diagnosis: The physician uses clinical reasoning to rule out various conditions based on the gathered evidence.

- Treatment Plan: This may involve prescribing pharmaceuticals, ordering imaging studies, or referring the patient to a specialist.

Levels of Care and Specialties

The medical field is organized into several tiers to manage the complexity of human health:

- Primary Care: The “first contact” for most patients, typically involving General Practice doctors who treat minor acute illnesses and manage long-term health education.

- Secondary Care: Specialized services (like cardiology or neurology) provided by experts to whom primary care doctors refer patients.

- Tertiary Care: Highly specialized care in regional centers for complex conditions, such as organ transplants or advanced trauma care.

Legal and Ethical Frameworks

The “practice of medicine” is a legally protected term. In most jurisdictions, including the US and UK, individuals must possess a medical degree and a license from a regulatory board to legally practice. This protects the public from “charlatans” and ensures practitioners meet national standards.

Ethically, the practice is guided by four core pillars for 2 Years DMS Course

- Autonomy: Respecting the patient’s right to choose or refuse treatment.

- Beneficence: Acting in the patient’s best interest.

- Non-maleficence: The classic oath of “First, do no harm”.

- Justice: Ensuring the fair distribution of health resources.

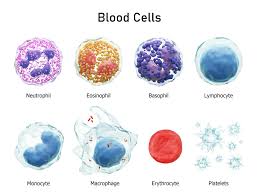

Hematology and Pathology for Medical Practice for 2 Years DMS Course

Hematology for 2 Years DMS Course

Hematology is a vast and intricate medical discipline dedicated to the study of blood, blood-forming tissues such as the bone marrow, and the complex systems that manage bleeding and clotting. It is a unique field that bridges the gap between laboratory science and direct clinical care, as blood—a liquid tissue—circulates throughout the entire body, interacting with every other organ and system.

Because blood is the body’s primary transport system for oxygen, nutrients, and waste, hematology is fundamental to diagnosing a wide array of conditions, from common iron deficiencies to rare genetic clotting disorders and aggressive cancers like leukemia.

Core Areas of Study

The subject of hematology is typically divided into several key pillars that encompass both normal physiology and pathological states:

- Hematopoiesis: This is the study of how blood cells are formed, primarily within the “spongy” core of the bones known as bone marrow. Specialists examine the lifecycle of stem cells as they differentiate into various functional blood components.

- Red Blood Cell (RBC) Disorders: Often referred to as “benign” or “classical” hematology, this area focuses on conditions affecting oxygen transport, such as anemia (the most common blood disorder), thalassemia, and sickle cell disease.

- Malignant Hematology (Hemato-Oncology): This subspecialty deals with cancers of the blood and lymphatic systems. This includes:

- Leukemia: Cancer involving the rapid production of abnormal white blood cells.

- Lymphoma: Cancer of the lymph nodes and lymphatic system.

- Multiple Myeloma: Cancer originating in the plasma cells of the bone marrow.

- Hemostasis and Thrombosis: This area investigates the mechanisms of blood clotting (coagulation). It covers bleeding disorders like hemophilia and von Willebrand disease, as well as clotting disorders such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

- Transfusion Medicine: This involves the science of blood groups (A, B, AB, O, and Rh factors) and the safe administration of blood products from donors to patients.

Diagnostic Procedures and Tests

Hematology relies heavily on precise laboratory analysis to “solve mysteries” regarding a patient’s health.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): The most fundamental test, measuring levels of white blood cells (WBCs), red blood cells (RBCs), platelets, hemoglobin, and hematocrit.

- Peripheral Blood Smear: A drop of blood is spread on a slide and examined under a microscope to look for abnormalities in cell shape, size, or maturity.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy: A procedure where a needle is used to extract a small sample of bone marrow to diagnose complex conditions like leukemia or bone marrow failure.

- Coagulation Tests: Tests like Prothrombin Time (PT) and Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT) measure how long it takes for blood to clot.

Educational and Career Pathways

Becoming a specialist in this field—known as a hematologist—requires extensive medical training. In most regions, this involves a four-year medical degree followed by a three-year residency in internal medicine or pediatrics, and then a two-to-three-year fellowship in hematology.

The field is rapidly evolving in 2025 with breakthroughs in molecular hematology, including gene therapy for hemophilia and CAR-T cell therapy, which uses genetically modified T-cells to attack cancer cells. This makes it an exciting but emotionally demanding career choice, often involving the care of patients with life-threatening illnesses.

For those interested in further study, resources like the American Society of Hematology (ASH) provide extensive educational materials and clinical guidelines.

In summary, hematology is a vital and dynamic subject that combines the precision of laboratory diagnostics with the humanity of patient care, serving as a critical cornerstone of modern medicine. Do you have more specific questions about a particular blood disorder or the training required to enter this field?

Pathology for Medical Practice for 2 Years DMS Course

Pathology is often described as the “bridge” between basic science and clinical medicine, serving as the essential foundation for nearly all medical practice. It is the study of disease—specifically its causes (etiology), mechanisms of development (pathogenesis), and the structural and functional changes it inflicts on cells and tissues. In modern healthcare, over 70% of all medical decisions—including diagnosis and treatment plans—rely on pathology investigations.

Core Branches of Medical Pathology

Pathology is broad and is typically divided into two primary categories, though many practitioners (general pathologists) work across both:

- Anatomical (Anatomic) Pathology: Focuses on the physical examination of organs and tissues.

- Surgical Pathology: Examining tissue removed during surgery (biopsies or resections) to identify disease, particularly cancer.

- Cytopathology: Studying individual cells from fluids or smears (e.g., Pap smears) to detect abnormalities.

- Forensic Pathology: Performing post-mortem examinations (autopsies) to determine the cause of death for legal or medical purposes.

- Clinical Pathology: Centered on the laboratory analysis of bodily fluids such as blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid.

- Chemical Pathology: Analyzing biochemical markers like electrolytes, enzymes, and hormones.

- Hematology: Diagnosing disorders of the blood and bone marrow, such as anemia or leukemia.

- Microbiology: Identifying infectious agents like bacteria, viruses, and fungi to guide antibiotic therapy.

The Pathologist’s Role in Patient Care

Often called the “doctor’s doctor,” pathologists work behind the scenes to guide primary physicians and surgeons. Their work is not limited to identifying a disease but extends to:

- Diagnosis: Determining exactly “what it is” by looking at cellular and molecular markers.

- Prognosis: Predicting how a disease will behave based on its specific characteristics.

- Treatment Selection: Identifying specific genetic mutations that might make a tumor vulnerable to targeted therapies (Precision Medicine).

- Monitoring: Analyzing repeated blood tests to track whether a treatment is working or if a disease is progressing.

Evolution into the 21st Century

Modern pathology is rapidly moving beyond the microscope into the realm of Molecular Pathology and Informatics.

- Molecular Pathology: Uses DNA and RNA sequencing to find the underlying genetic cause of diseases, which is now essential for modern cancer care.

- Digital Pathology: Involves scanning slides into high-resolution images for remote consultation (telepathology) and applying Artificial Intelligence (AI) to help identify patterns or biomarkers invisible to the human eye.

Career and Training

Becoming a pathologist is a long and rigorous process, typically requiring 11 to 13 years of education. This includes:

- Undergraduate Degree: Usually 4 years in a biological or chemical science.

- Medical School: 4 years to earn an MD or DO degree.

- Residency: 3 to 4 years of specialized pathology training.

- Fellowship (Optional): 1 to 2 years of further subspecialization in areas like neuropathology or dermatopathology.

Despite being an “invisible” specialty with limited direct patient contact, the field offers high job satisfaction due to its detective-like nature and critical impact on public health. Top-tier subspecialties like Neuropathology are among the highest-paid roles in the field.

Surgery-1 and Antimicrobial Drugs for 2 Years DMS Course

Surgery for 2 Years DMS Course

Surgery, a term often used interchangeably with “operation,” represents one of the most critical and intricate branches of modern medicine. It is a discipline that utilizes manual and instrumental techniques to investigate, diagnose, or treat pathological conditions, such as injuries or diseases. While many people associate the word with high-stakes hospital environments, the field encompasses everything from life-saving emergency interventions to routine diagnostic biopsies performed in a doctor’s office.

The evolution of surgery has transformed it from a risky, often agonizing “art” into a precise scientific discipline. Historically, the three greatest barriers to successful surgery were pain, infection, and blood loss. Today, with the advent of advanced anesthesia, sterile techniques (antisepsis), and sophisticated tools like lasers and robotics, surgeons can perform procedures that were once considered impossible.

The Scope and Goals of Surgery for 2 Years DMS Course

Surgeons do not just “cut”; they engage in a continuum of care that includes diagnosis, preparation, the procedure itself, and the subsequent recovery period. The primary goals of these interventions typically fall into several broad categories:

- Curative and Extirpative: The removal of diseased tissue or organs, such as taking out an infected appendix or a cancerous tumor.

- Diagnostic: Procedures like biopsies where a small piece of tissue is removed for examination under a microscope to confirm a diagnosis.

- Reconstructive: Restoring function or appearance after an injury, burn, or disease, such as repairing a broken bone with metal rods or performing plastic surgery.

- Palliative: Surgery intended to reduce pain or improve quality of life, even if the underlying disease (like advanced cancer) cannot be fully cured.

- Transplantation: The replacement of a failing organ with a healthy one from a donor.

Classifying Surgical Procedures 2 Years DMS Course

To better understand the risks and requirements of a specific operation, medical professionals often categorize surgeries based on their urgency and the approach taken:

- Timing and Urgency:

- Elective Surgery: These are planned procedures that can be scheduled in advance. While “elective” sounds optional, it often includes necessary treatments like joint replacements or even some cancer removals that are not immediate emergencies.

- Emergency Surgery: This is surgery that must be performed immediately to prevent death or serious disability, such as repairing internal bleeding from a car accident.

- Surgical Approach:

- Open Surgery: The traditional method involving a single, large incision to allow the surgeon direct access to the internal organs.

- Minimally Invasive Surgery (Keyhole Surgery): The surgeon makes several small cuts and uses a laparoscope—a thin tube with a camera and light—to see inside. Instruments are then inserted through the other small holes to perform the work, typically leading to faster recovery times.

The Surgical Team and Process 2 Years DMS Course

A modern surgical operation is a team effort. The surgical team typically includes a lead surgeon, a surgical assistant, an anesthesiologist, a scrub nurse to handle sterile equipment, and a circulating nurse to manage the room.

Before the procedure, patients undergo a process of “informed consent,” where the doctor explains the benefits and risks. Post-operative care is equally vital, focusing on wound care, pain management, and physical rehabilitation. Recovery times vary wildly: a minor biopsy might heal in days, whereas a total knee replacement can take months to a full year for a complete return to normal.

Risks and Modern Considerations

Despite high success rates, all surgeries carry inherent risks, including infection, excessive bleeding, or adverse reactions to anesthesia. Recent medical advisories in 2025 have highlighted specific new concerns, such as the increased risk of pulmonary aspiration during surgery for patients taking GLP-1 weight-loss drugs like Ozempic.

In summary, surgery remains a cornerstone of medical treatment, continuously advancing through technology to become safer and less invasive. If you are facing surgery, it is always recommended to seek detailed information from your healthcare provider and, when possible, a second opinion to understand all your treatment options

Antimicrobial Drugs for 2 Years DMS Course

Antimicrobial drugs represent one of the most significant advancements in the history of medicine, fundamentally altering the human experience by making once-fatal infections manageable and often curable. At its core, an antimicrobial is any substance—whether natural, semisynthetic, or fully synthetic—that is designed to kill or inhibit the growth of microorganisms. This “umbrella” term encompasses a wide range of medications tailored to specific types of pathogens: bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites.

The primary goal of antimicrobial therapy is selective toxicity, the ability of a drug to kill or inhibit the pathogen without causing significant damage to the host. This is achieved by targeting biological structures or metabolic pathways that are unique to the microbe and absent in human cells. For instance, many antibiotics target the bacterial cell wall—a structure humans do not have—while others target specific bacterial ribosomes that differ from our own.

Core Classifications of Antimicrobial Drugs for 2 Years DMS Course

Antimicrobial drugs are categorized based on the type of organism they target, their chemical structure, and their specific mode of action.

- Antibiotics (Antibacterials): These are the most common antimicrobials and specifically target bacteria. They are further divided into:

- Bactericidal agents: These drugs directly kill the bacteria (e.g., penicillins, cephalosporins).

- Bacteriostatic agents: These drugs inhibit the reproduction of bacteria, allowing the host’s immune system to clear the infection (e.g., tetracyclines, macrolides).

- Antifungals: These medications treat infections caused by fungi, such as yeasts or molds. Because fungi are eukaryotic—meaning their cell structure is more similar to human cells—developing antifungals with selective toxicity is more challenging than developing antibiotics, often leading to more side effects. Common examples include fluconazole and ketoconazole.

- Antivirals: Viruses are obligate intracellular pathogens, meaning they reproduce inside host cells using the host’s own machinery. Antiviral drugs must therefore inhibit viral replication without destroying the host cell itself. Famous examples include acyclovir for herpes and various antiretroviral therapies (ART) for HIV.

- Antiparasitics: This class includes drugs to treat infections from protozoa (like malaria) and helminths (worms). Medications like chloroquine and ivermectin belong to this group.

Key Mechanisms of Action

Antimicrobials disrupt the life cycle of pathogens through several sophisticated biochemical strategies:

- Inhibition of Cell Wall Synthesis: Drugs like penicillin and vancomycin prevent the formation of peptidoglycan, an essential component of the bacterial cell wall, causing the cell to burst under osmotic pressure.

- Inhibition of Protein Synthesis: These agents bind to either the 30S or 50S subunits of bacterial ribosomes, stopping the translation of genetic code into the proteins necessary for life. Examples include doxycycline and azithromycin.

- Inhibition of Nucleic Acid Synthesis: Some drugs block the enzymes needed to replicate DNA or transcribe RNA. Ciprofloxacin, for instance, inhibits DNA gyrase, while rifampin blocks RNA polymerase.

- Disruption of Cell Membranes: Certain agents, like polymyxin B, damage the integrity of the microbial cell membrane, causing vital nutrients to leak out.

- Inhibition of Metabolic Pathways: Antimetabolites like sulfonamides (sulfa drugs) mimic the structures of natural compounds to trick microbes into a “starvation” state, notably by blocking folic acid synthesis.

The Global Challenge: Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

Perhaps the most critical topic in modern microbiology is Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). AMR occurs when microorganisms evolve mechanisms to survive exposure to drugs that should have killed them. This is a natural evolutionary process accelerated by the misuse and overuse of these drugs in humans, animals, and agriculture.

Common resistance mechanisms include producing enzymes that destroy the drug (like β-lactamase), pumping the drug out of the cell (efflux pumps), or changing the drug’s target site so it can no longer bind. In 2025, AMR remains a top-tier public health threat, directly contributing to millions of deaths annually and threatening to return medicine to a “pre-antibiotic era” where simple surgeries and infections become life-threatening once again

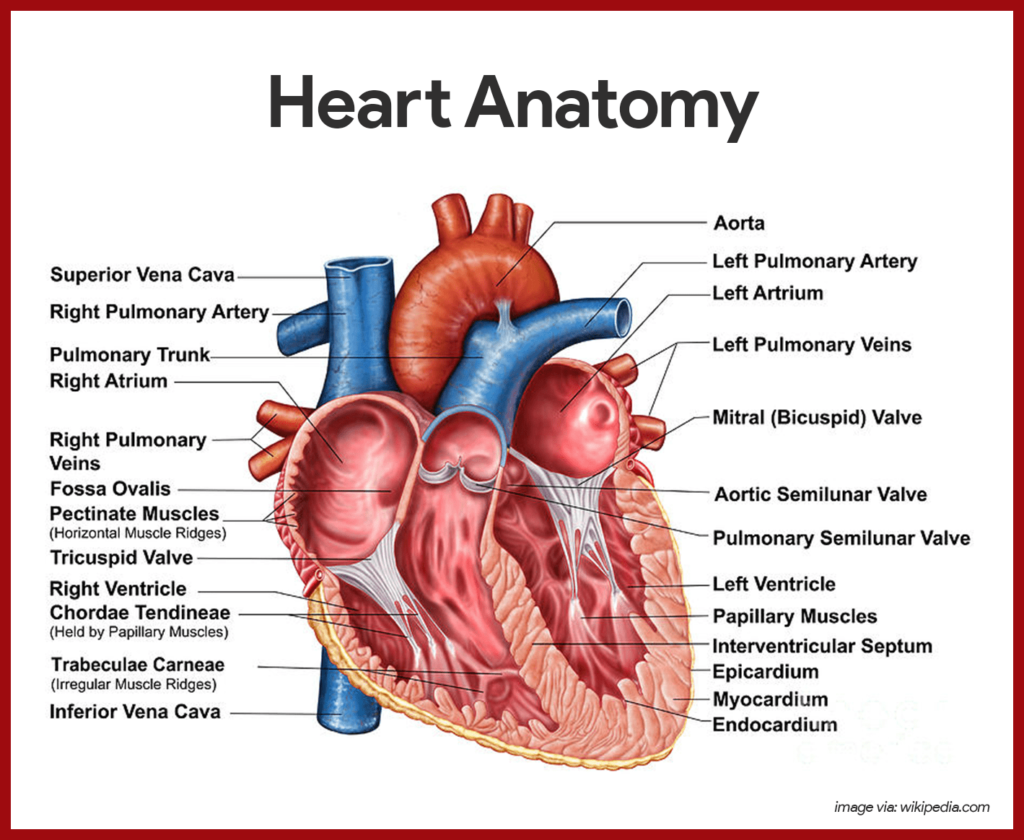

Cardiovascular Anatomy for 2 Years DMS Course

The cardiovascular system, often interchangeably referred to as the circulatory system, serves as the body’s primary transportation network, ensuring that every cell receives the oxygen and nutrients required for survival while efficiently removing metabolic waste products like carbon dioxide. This complex physiological machine is comprised of the heart, a network of blood vessels, and the blood itself.

At its core, cardiovascular anatomy is an study of fluid dynamics and mechanical engineering. The heart acts as a dual-action pump, circulating blood through two distinct but interconnected loops: the pulmonary circulation, which exchanges gases in the lungs, and the systemic circulation, which services the rest of the body’s tissues.

The Heart: The Central Pump

The human heart is a hollow, muscular organ roughly the size of a large clenched fist, weighing between 250 and 350 grams. It is situated in the mediastinum, the central compartment of the thoracic cavity, behind the sternum and between the lungs.

- Heart Walls and Layers: The heart is protected by the pericardium, a double-layered sac containing a small amount of lubricating fluid to reduce friction during beats. The wall of the heart itself consists of three distinct layers:

- Epicardium: The thin, protective outer layer.

- Myocardium: The thick middle layer composed of specialized cardiac muscle tissue responsible for the powerful contractions that pump blood.

- Endocardium: The smooth inner lining of the chambers and valves, which is continuous with the endothelial lining of the blood vessels.

- Chambers of the Heart: The heart is divided into four chambers—two superior atria and two inferior ventricles.

- Right Atrium: Receives deoxygenated blood from the body via the superior and inferior venae cavae.

- Right Ventricle: Receives blood from the right atrium and pumps it into the pulmonary trunk toward the lungs.

- Left Atrium: Receives oxygen-rich blood returning from the lungs through the pulmonary veins.

- Left Ventricle: The largest and thickest-walled chamber; it pumps oxygenated blood with great force through the aorta to the entire systemic circulation.

- The Valvular System: Four valves act as one-way “doors” to ensure blood moves in only one direction.

- Atrioventricular (AV) Valves: These include the tricuspid valve (right side) and the mitral valve (left side), which prevent blood from flowing back into the atria when the ventricles contract.

- Semilunar Valves: These include the pulmonary valve and the aortic valve, located at the exits of the ventricles to prevent backflow from the great vessels during the relaxation phase.

The Vascular Network: Arteries, Veins, and Capillaries

Blood vessels form a vast network that, if laid end-to-end, would extend for approximately 60,000 miles. They are categorized based on their structure and the direction of blood flow.

- Arteries: These muscular vessels carry blood away from the heart. Because they must withstand high pressure, they have thick, elastic walls. The aorta is the largest artery in the body. As arteries branch further from the heart, they become smaller arterioles, which are key regulators of blood pressure.

- Capillaries: These are the smallest vessels, with walls only one cell thick. They are the site of actual exchange where oxygen and nutrients pass into tissues and waste products enter the bloodstream.

- Veins: These vessels return blood to the heart. Since blood pressure in veins is much lower than in arteries, they have thinner walls and often feature one-way valves to prevent backflow, especially in the limbs where blood must move against gravity.

Electrical Conduction and the Cardiac Cycle

The heart does not require external nerve signals to beat; it has its own intrinsic electrical system.

- Sinoatrial (SA) Node: Located in the right atrium, it is the heart’s “natural pacemaker,” initiating the electrical impulse for each beat.

- Atrioventricular (AV) Node: This node delays the electrical signal slightly, allowing the atria to fully contract and empty blood into the ventricles before the ventricles contract.

- Bundle of His and Purkinje Fibers: These specialized fibers distribute the electrical impulse rapidly throughout the ventricles, ensuring a coordinated, powerful contraction.

The rhythmic cycle of the heart is divided into two phases: systole (contraction and ejection of blood) and diastole (relaxation and filling of the chambers).

Coronary Circulation: Feeding the Heart

The heart muscle itself requires a constant supply of oxygenated blood. This is provided by the coronary arteries, which branch directly from the base of the aorta. The left main coronary artery and the right coronary artery supply different regions of the myocardium. Deoxygenated blood from the heart tissue is collected by cardiac veins and drains into the coronary sinus, which empties into the right atrium.

In summary, cardiovascular anatomy describes a highly specialized system designed for the continuous, life-sustaining movement of blood. From the muscular prowess of the left ventricle to the delicate exchange at the capillary level, every component is critical for maintaining homeostasis. Understanding these structures provides the foundation for diagnosing and treating a wide range of cardiovascular diseases, from valve abnormalities to coronary artery blockages. If you have further questions about specific components like fetal circulation or the mechanics of heart sounds, feel free to ask!

Medical Diagnosis-1&2 for 2 Years DMS Course

Medical diagnosis is a fundamental cognitive and procedural cornerstone of healthcare, representing the dynamic process of identifying the nature and cause of a patient’s illness. In essence, it is a high-level form of problem-solving where a clinician “discerns” (from the Greek diagignōskein) the differences between health and disease or distinguishes one specific pathology from another. This intricate journey translates the “external language” of a patient’s symptoms and observable signs into the “internal language” of medical science and pathology.

The Multi-Step Diagnostic Process

The modern diagnostic procedure is rarely a singular event but rather a cyclical, iterative journey involving several core phases to reduce uncertainty:

- Clinical History and Interview: This is often the most critical step, where the clinician gathers a detailed account of the present illness, past medical history, family genetics, social lifestyle, and medication use. It has been said that a patient’s own history can “trump” expensive investigations if carefully listened to.

- Physical Examination: A hands-on assessment where the clinician collects vital signs (like heart rate and blood pressure) and uses techniques such as inspection, palpation (feeling), percussion (tapping), and auscultation (listening with a stethoscope) to identify physical abnormalities.

- Differential Diagnosis: Using the initial data, the provider creates a “differential diagnosis”—a prioritized list of possible conditions that could explain the symptoms.

- Diagnostic Testing: To narrow this list, targeted tests are ordered. These range from laboratory work (blood, urine) and medical imaging (X-rays, CT scans, MRIs) to specialized biopsies or neurocognitive assessments.

- Deduction and Verification: The final step involves integrating all collected evidence to arrive at a “working diagnosis.” If a treatment plan is initiated, the patient’s response to it serves as a final “feedback loop” to confirm or refine the original diagnostic theory.

Cognitive Approaches to Diagnosis

Clinicians utilize two primary cognitive frameworks, often referred to as “Dual Process Theory”:

- System 1 (Intuitive): This is fast, unconscious pattern recognition used by experienced doctors for “obvious” cases—for example, instantly recognizing a bull’s-eye rash as Lyme disease.

- System 2 (Analytic): This is slow, deliberate, and logical reasoning. It is activated when a case is complex or unusual, requiring the clinician to methodically test hypotheses and appraise evidence.

Modern Challenges and Innovations

Despite its critical importance, the process is fraught with potential for error. Diagnostic errors—either failing to establish an accurate explanation or failing to communicate it—affect most people at least once in their lives. Common pitfalls include:

- Cognitive Biases: Such as “anchoring bias,” where a doctor relies too heavily on their first impression and ignores later conflicting data.

- Over diagnosis: Labeling a “disease” that will never actually cause harm or symptoms during a patient’s life, which can lead to unnecessary treatment and anxiety.

- The “Diagnostic Odyssey”: A term used for cases where a diagnosis takes an excessively long time to reach, often seen with rare diseases.

To combat these challenges, 2025 sees an increasing integration of Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS) and Artificial Intelligence. These tools use machine learning to help clinicians process vast amounts of data and suggest prioritized differential lists, though they are designed to support—not replace—human clinical judgment.

Summary of Diagnostic Significance

A proper diagnosis is not just a label; it is the prerequisite for an effective treatment plan, a prediction of the disease’s course (prognosis), and a means of reducing patient anxiety by providing clarity. Whether it is a clinical diagnosis based on signs, a laboratory diagnosis from test results, or a radiological diagnosis from imaging, the ultimate goal remains “diagnostic excellence”—achieving care that is safe, timely, equitable, and patient-centered.

Chemistry and Medical Biochemistry for 2 Years DMS Course

Chemistry for 2 Years DMS Course

Chemistry is the scientific study of matter, its properties, composition, and the transformations it undergoes during chemical reactions. Often called the central science, it bridges the gap between physics and biology, providing a foundation for fields like medicine, environmental science, and forensics.

Core Branches

Chemistry is traditionally divided into five main sub-disciplines:

- Organic Chemistry: The study of carbon-based compounds, including most chemicals found in living organisms.

- Inorganic Chemistry: Focuses on compounds that generally do not contain carbon, such as minerals and metals.

- Physical Chemistry: Applies the principles of physics (like thermodynamics and quantum mechanics) to understand chemical systems.

- Analytical Chemistry: The science of identifying and quantifying the composition of matter.

- Biochemistry: Explores the chemical processes that occur within living organisms.

Fundamental Concepts

- Atoms & Elements: The atom is the basic unit of chemistry. Elements are pure substances made of only one type of atom, organized in the Periodic Table.

- Chemical Bonds: Interactions that hold atoms together, primarily categorized as ionic (electron transfer) or covalent (electron sharing).

- Chemical Reactions: Processes where substances (reactants) are transformed into new substances (products) through the rearrangement of chemical bonds.

- The Mole: A fundamental unit of measurement

History and Evolution

Chemistry evolved from the ancient practice of alchemy, which sought to transmute base metals into gold. The transition to modern science occurred during the 17th and 18th centuries with pioneers like Robert Boyle, who championed the scientific method, and Antoine Lavoisier, known for the law of conservation of mass

Medical Biochemistry for 2 Years DMS Course

Medical biochemistry is a critical branch of medicine and biology that explores the chemical processes within and relating to living organisms, specifically focusing on human health and disease. By examining how biological molecules—such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—interact, medical biochemists can uncover the molecular roots of various pathologies, leading to more effective diagnostic tools and therapeutic treatments.

The Scope of Medical Biochemistry

This field acts as a bridge between basic science and clinical practice. It involves a deep dive into the following core areas:

- Metabolism and Energy Production: The study of how the body converts nutrients into energy through complex pathways like the citric acid cycle and the electron transport chain. Understanding these cycles is vital for treating metabolic disorders like diabetes.

- Molecular Genetics and Genomics: Investigating the structure and function of DNA and RNA to understand how genetic information is transferred and how mutations lead to hereditary diseases.

- Enzymology: Analyzing enzymes as biological catalysts that speed up chemical reactions. Medical biochemistry looks at how enzyme regulation—or its failure—impacts health.

- Nutritional Biochemistry: Examining the role of vitamins and minerals as essential co-factors for body functions, including DNA formation and hormonal regulation.

Clinical Applications and Diagnostics for 2 Years DMS Course

Medical biochemistry is indispensable in modern healthcare for diagnosing and monitoring diseases. Practitioners, often called clinical biochemists or medical biochemists, operate in hospital laboratories to analyze patient samples.

- Biomarker Analysis: Measuring specific substances in blood, urine, or tissues (analytes) to identify conditions like kidney dysfunction (via uric acid levels), liver disease, or heart conditions.

- Drug Development and Toxicology: Studying chemical interactions between substances and the body to determine a drug’s metabolism, half-life, and potential toxic effects.

- Pathology Investigation: Uncovering the molecular basis of varied conditions, including sickle cell anemia, atherosclerosis, and jaundice.

Careers and Professional Development

As of 2025, the demand for medical biochemists continues to grow across several sectors:

- Healthcare Centers: Working in diagnostic labs to support patient care and interpret test results for physicians.

- Pharmaceutical Industry: Designing and testing new medications and vaccines.

- Academic Research: Investigating complex biological problems, such as cancer biology or neuroprotection for brain disorders like Alzheimer’s.

- Forensics and Biotechnology: Applying biochemical techniques to solve crimes or develop new bio-engineered tools.

Educational pathways typically involve specialized undergraduate degrees (BSc in Medical Biochemistry), often followed by postgraduate training or clinical residencies for those pursuing leadership roles in hospital medicine.

Medical biochemistry remains at the heart of medical innovation, providing the necessary chemical framework to understand life itself and the many ways it can be preserved and restored. For those interested in pursuing this field, resources like The Medical Biochemistry Page provide extensive portals for deeper study.

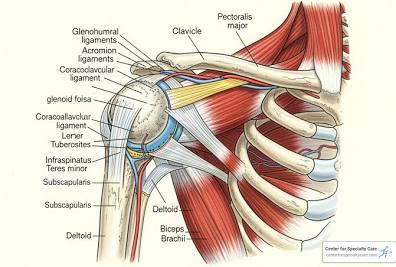

Orthopedic Anatomy for 2 Years DMS Course

Orthopedic anatomy is the specialized study of the human musculoskeletal system, a complex network of tissues that provides the body with structural support, protection for vital organs, and the mechanical means for movement. At its core, this discipline integrates the study of macroscopic (gross) structures—such as the 206 bones in the adult skeleton—with microscopic details like the composition of collagen fibers and the mineralized matrix of bone tissue. Understanding these structures is foundational for diagnosing and treating injuries like fractures, sprains, and chronic conditions like arthritis.

The musculoskeletal system is comprised of several critical components for 2 Years DMS Course

- Bones and the Skeleton: The adult skeleton serves as the rigid framework of the body. Long bones, such as the femur, are particularly significant in orthopedics; they grow from epiphyseal plates (growth plates) and are divided into segments: the epiphysis (ends), diaphysis (shaft), and metaphysis (the transitional zone).

- Joints (Articulations): These are the sites where two or more bones meet. They vary significantly in their range of motion, from highly mobile ball-and-socket joints like the shoulder and hip to hinge joints like the elbow that primarily allow flexion and extension.

- Connective Tissues: These include ligaments, which connect bone to bone to stabilize joints; tendons, which anchor muscles to bones to transmit force; and cartilage, which provides a smooth, low-friction bearing surface within joints.

- Muscles: The body contains roughly 640 muscles. Skeletal muscles are voluntary and function in pairs (agonists and antagonists) to produce movement while also providing essential joint stability.

Visual Overview of Orthopedic Anatomy

Orthopedic specialists often focus on specific regions of the body due to their unique mechanical demands and common injury patterns:

- The Knee Joint: This complex hinge joint relies heavily on stabilizing ligaments, including the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) and Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL). It also features specialized C-shaped cartilage called the meniscus, which acts as a shock absorber.

- The Shoulder: Known for its extreme mobility, the shoulder is a “shallow” ball-and-socket joint. Its stability depends largely on the rotator cuff (a group of four muscles: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis) and the labrum, a fibrocartilaginous rim that deepens the socket.

- The Spine: This central axis supports the head and torso while protecting the spinal cord. It is a frequent focus of orthopedic care for conditions ranging from deformities like scoliosis to age-related degenerative changes.

For those pursuing clinical expertise, resources like the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) provide extensive patient education materials, while academic platforms such as Orthobullets offer specialized anatomical dashboards and surgical technique guides for medical professionals.

This overview barely scratches the surface of the intricate mechanics and biological processes—such as Wolff’s Law, which describes how bone remodels in response to stress—that define the field of orthopedics. Whether you are interested in the cellular level of bone mineralization or the macroscopic repair of a complex fracture, orthopedic anatomy remains one of the most dynamic and vital areas of medical study. Feel free to ask if you would like to dive deeper into any specific joint or muscle group.

General Pathology-1 for 2 Years DMS Course

General pathology serves as the foundational “bridge” between basic biological sciences and clinical medical practice. It is the scientific study of the basic responses of cells and tissues to abnormal stimuli—the fundamental mechanisms that underlie all human diseases. While specialized branches of medicine focus on specific organ systems, general pathology examines the universal processes that occur regardless of the organ involved, such as how a cell dies, why an area becomes inflamed, or how a tumor begins to grow.

In a diagnostic setting, general pathology often describes a broad field where a single practitioner manages multiple aspects of laboratory medicine, including anatomical pathology (examining tissues) and clinical pathology (analyzing bodily fluids like blood and urine). This “jack-of-all-trades” approach is essential in community or district hospitals where a pathologist must be capable of diagnosing a wide variety of cases, from identifying cancerous cells in a biopsy to managing complex blood transfusion protocols.

The Four Pillars of Disease for 2 Years DMS Course

To provide a complete explanation of any disease, general pathology follows four core aspects that guide every investigation:

- Etiology (The “Why”): This refers to the primary cause of a disease. Etiologies can be genetic (inherited mutations) or acquired (infectious agents like bacteria, physical trauma, or chemical toxins). If a cause cannot be identified, the condition is termed idiopathic.

- Pathogenesis (The “How”): This is the sequence of events and the mechanism by which the cause operates to produce the disease. It describes how the initial cellular stress evolves into full-blown symptoms.

- Morphologic Changes (The Appearance): These are the structural alterations in cells or tissues that can be seen with the naked eye (gross pathology) or under a microscope (histopathology). For example, the presence of specific granulomas can be a hallmark sign of tuberculosis.

- Clinical Significance (The Impact): This refers to the functional consequences of the morphologic changes, which lead to the signs and symptoms observed by the patient and doctor.

Core Concepts and Mechanisms for 2 Years DMS Course

General pathology is typically categorized into several broad thematic areas that occur across all organ systems:

- Cell Injury and Adaptation: Cells constantly adjust to their environment to maintain homeostasis. When stressed, they may adapt through processes like hypertrophy (increase in cell size) or hyperplasia (increase in cell number). If the stress is too severe, the injury becomes irreversible, leading to cell death via necrosis or apoptosis. Hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) is cited as the most common cause of cell injury.

- Inflammation and Repair: This is the body’s protective response to eliminate the cause of injury and clear out dead tissue. It includes acute inflammation (characterized by redness, heat, swelling, and pain) and chronic inflammation, followed by healing processes like scarring.

- Hemodynamic Disorders: These involve disturbances in blood flow and fluid balance, such as thrombosis (blood clots), embolism, and edema (swelling).

- Neoplasia: The study of tumors, both benign and malignant. General pathology examines the genetic and cellular triggers that allow cells to grow uncontrollably.

- Immunopathology: The study of diseases caused by a malfunctioning immune system, such as allergies or autoimmune diseases like lupus.

Diagnostic Modalities

Pathologists use a wide range of tools to identify disease markers:

- Histopathology: Microscopic examination of tissue sections, often obtained through a biopsy.

- Cytopathology (Cytology): Studying individual cells from fluids or smears (like a Pap smear).

- Clinical Biochemistry: Analyzing chemical substances in the blood, such as glucose, proteins, and electrolytes.

- Molecular Pathology: A modern discipline using DNA and RNA analysis to identify genetic mutations or pathogens.

- Forensic Pathology: Determining the cause of death through an autopsy.

Pathology is a deeply educational field; its pioneers, like Hippocrates (the “Father of Medicine”), shifted the understanding of disease from “evil spirits” to observable biological changes. Today, a general pathologist is an indispensable consultant to other doctors, providing the definitive diagnosis that determines a patient’s entire treatment plan.

Whether you are interested in the cellular “detective work” of finding a hidden cancer or understanding the broad mechanisms of how humans heal, general pathology provides the essential toolkit for all of modern medicine. If you have specific questions about any of these branches or how certain tests are performed, feel free to ask.

Pharmacology-2 for 2 Years DMS Course

In the vast and intricate world of medical education, Pharmacology-II represents a critical bridge between foundational drug science and its practical, life-saving application in complex organ systems. While the first phase of pharmacology typically introduces you to the broad “rules” of how drugs behave—concepts like absorption, metabolism, and receptor binding—Pharmacology-II dives deep into the specific toolkits used to treat diseases of the heart, the lungs, the endocrine system, and beyond. It is often regarded by students as one of the most challenging but rewarding semesters, as it transforms abstract chemical formulas into tangible treatments for conditions like heart failure, diabetes, and severe infections.

This discipline is designed to provide you with a systemic understanding of how therapeutic agents modify biological functions to restore health or manage chronic illness. Whether you are a pharmacy student, a medical trainee, or a nursing professional, mastering Pharmacology-II means moving beyond simple memorization to understanding the “why” behind every prescription.

The Core Pillars of Pharmacology-II for 2 Years DMS Course

The curriculum of Pharmacology-II is typically structured around the major physiological systems of the body. Each unit focuses on the pathophysiology of a system and the specific drugs used to manipulate it.